Planes of Content and Expression

Develop your knowledge and understanding of Louis Hjelmslev’s sign theory.

Introduction

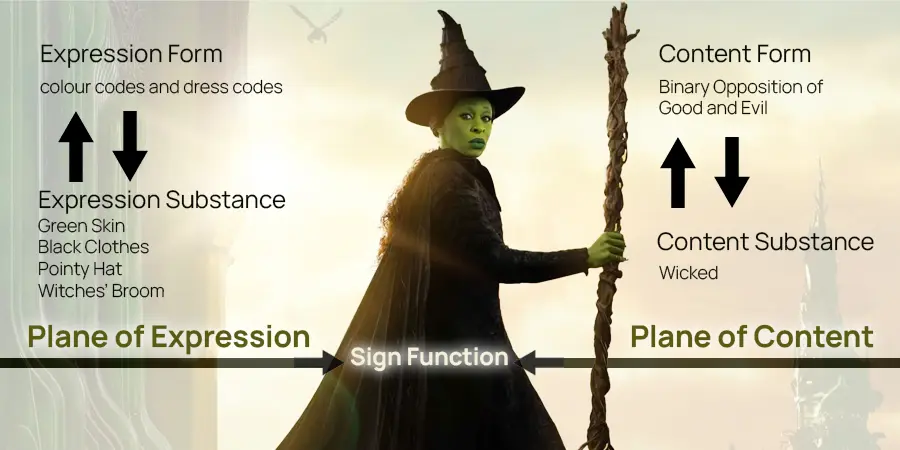

Louis Hjelmslev (1961) considered language to be “the ultimate and deepest foundation of human society” and was determined to “grasp the totality” of the system and its processes. He argued a sign was a “two-sided entity” connecting a plane of content with a plane of expression.

- The plane of content refers to the meaning or concept conveyed by the sign.

- The plane of expression is the physical production of a sign, such as sounds, letters, images, gestures, lighting, and anything else that can be used to communicate meaning.

Hjelmslev also believed signs only made sense because both their physical and conceptual sides were organised by systems, so he added form and substance to his model.

- Forms are the structures, rules, regulations, categories, and patterns that organise the content and expression.

- Substance is the realisation of content (actual thoughts and feelings) and expression (sounds or ink on a page).

We are going to use examples from Wicked (2024) to illustrate the logic of Hjelmslev’s theory, starting with the sign function and some straightforward examples of expression and content.

Contents

The Sign Function

Think about a memorable line from Wicked or any other film you have watched. Although you can conceptualise the words in your mind, they are not signs because they do not have a physical expression.

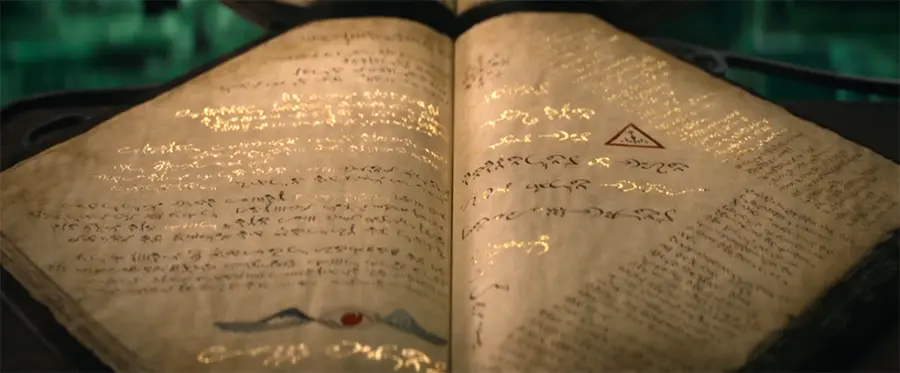

Towards the end of the film, the Grimmerie opens and Elphaba begins to read from the ancient book of wisdom, thaumaturgy and enchantments. Try uttering the phrase “ah ben tah kay” out loud. It’s gibberish. Just some magic invented by the writers. There is a physical expression, an arrangement of syllables and the suggestion of words, but the sounds “ah ben tah kay” have no meaningful content.

When Glinda looks at the pages, she asks, “Are those words?”

Like a stage magician saying abracadabra before they pull a rabbit out of a hat or a coin from behind someone’s ear, the words in the Grimmerie are meaningless. No-one can attach any specific content to the expressions.

Hjelmslev argued signs are “generated” by the connection between a physical expression and a mental concept, such as sounds, letters, images, gestures, lighting, and anything else that could be used to produce meaning.

A sign function must always have the “simultaneous presence” of expression and content.

Expression and Content

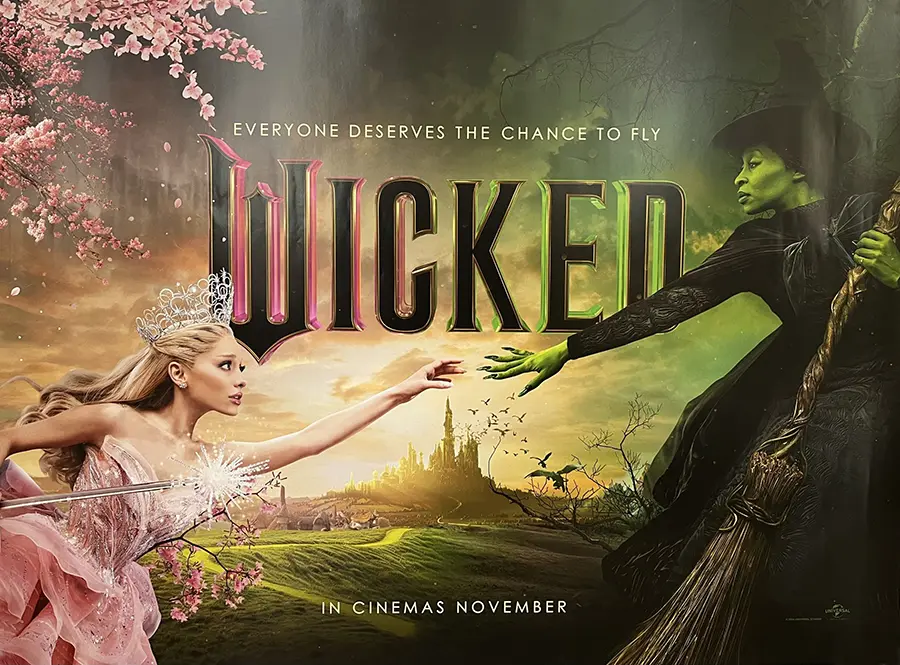

Wicked uses a variety of expressions to construct a clear contrast between the two protagonists. Elphaba’s green skin immediately marks her as different from others, making her a target of ridicule and fear. At the end of the first part, Madame Morrible declares “her green skin is but an outward manifestorium of her twisted nature”.

Glinda’s beauty is encoded in her pale skin. Everyone is “less fortunate” than her.

Elphaba has dark hair. Glinda is “toss, toss” blonde.

Elphaba’s clothes are dark and considered to be unfashionable by her peers. In the Ozdust scene, one student cruelly sneers, “Her hat is disgustifying.” Black is traditionally associated with immorality and corruption. By contrast, Glinda is always wearing something pink – a colour reinforcing her femininity.

Elphaba demonstrates maturity, such as supporting her sister and giving her space. Glinda has all the petulance of a child who likes to get her own way and then throws a tantrum when something challenges her ego.

When they arrive at the Emerald City, Elphaba is excited to visit the “libraries” and museums” whereas Glinda is impressed by the “dress salons” and “palaces”.

Colours, clothes, and gestures can be sign functions because they have a physical expression and communicate content. Of course, the story subverts our expectations and positions the audience to sympathise with a character we were taught to hate.

The Expression Substance

The expression substance refers to physical appearance of the sign, such as the skin colours, clothing and gestures that construct the binary opposition in our previous examples.

It is important to remember the relationship between the physical manifestation of the sign and its meaning is arbitrary. The social conventions and cultural values in the film determine dark clothing to be unfashionable and blonde hair to be more attractive.

There is no natural or logical connection between the combination of letters forming the word wicked and the concept of immorality in our minds. We simply accept the denotation as true. By using the expression wicked, we reinforce its definition.

Other languages use different letters, such as méchant in French and ilkeä in Finnish. The physical realisations of the signs are different, but they convey the same purport.

Hjelmslev insisted meaning is not fixed by the substance. It’s produced by the forms that organise both expression and content.

It is worth noting the substance of the expression is also shaped by the speaker. Consider the “pronouncification” of Galinda. The history professor, Dr Dilamond, is unable to sound the first syllable because he lacks upper front teeth and calls her Glinda instead.

The Expression Form

The expression form refers to how signs are constructed. The language system also determines the ways sequences are arranged.

Word Building

Type the phrase “no-one mourn the wicked” into your word processing program and you might see the grammar-checker has marked the word “mourn” with lines to identify the mistake. If it has not autocorrected, right-click the verb and the software will suggest the standard version: “no-one mourns the wicked”.

Either way, what you are seeing is the physical expression of the sign being determined by the conventions of English and how we build regular verbs.

Wicked deliberately plays with how words are constructed. For example:

- Glinda complains Fiyero has become “moodified” instead of moody and describes Elphaba’s magic as “astoundifying” and not “astounding”.

- Glinda asks how she can “express” her “gratitution” when she receives the training wand from Madame Morrible.

- Pfannee admires Glinda’s “braverism” and not bravery.

- Elphaba is summoned “most ceremonyishly” to see the Wizard.

These words are not “horrenible” or even “confusifying” because we still appreciate their content. They are just built according to different set of rules.

Importantly, these imaginative expressions in the film draw attention to how the physical realisation of signs is motivated by the language form.

“It becomes clear that the substance depends on the form to such a degree that it lives exclusively by its favor and can in no sense be said to have independent existence.”

Louis Hjelmslev (1961)

Hjelmslev also argued suffixes should be considered signs because they were generating content. This means there are two signifiers in mourn-s.

The projection of the system onto the sign can result in some complex expressions. In the word inactivates, for example, Hjelmslev identified “five distinguishable entities which each bear meaning and which are consequently five signs”:

- in is a prefix which means not or opposite of

- act is the root which means to do or to act

- ive is a suffix that helps form adjectives

- ate is a verb-forming suffix meaning to make or cause to be

- s is the third person singular present tense ending to be used with he, she, or it.

Hjelmslev wanted to emphasise this relationship by dividing the expression into two parts: the physical realisation of signs (substance) and the conventions of the language system (form).

Linguistic Chains

We combine signs into sentences and other sequences to communicate our thoughts and ideas. Each language also governs how the expressions are arranged and presented.

For example, in the final song, Elphaba sings “I am defying gravity”. The verb phrase is in the present continuous tense. However, French does not have a direct equivalent to this tense in English, so a translator might simply write je défie la gravité, meaning I defy gravity.

Interestingly, the French subtitles offer this translation of the line: je dois défier la gravité. The direct equivalent in English is I must defy gravity which emphasises her determination to fight against injustice in the Land of Oz.

Hjelmslev discussed how “linguistic chains” are formed differently in each language. The patterns of grammar and syntax stress different factors and “puts the centers of gravity in different places”.

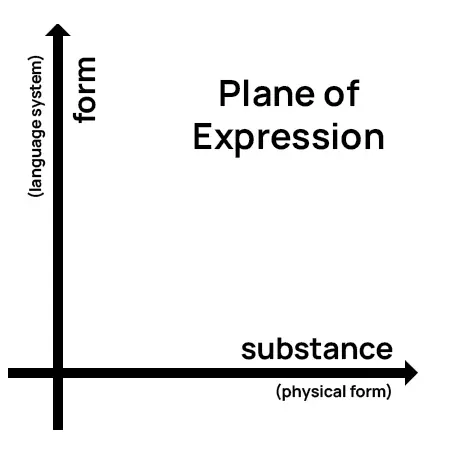

The Plane of Expression

In mathematics, a plane is a two-dimensional concept, so it is an appropriate word to convey the two-dimensions of expressions – form and substance.

Hjelmslev introduced the term expression to take account of how the physical realisation of signs is heavily influenced by the language system.

The Plane of Content

The plane of content is also two-dimensional.

The content substance is the raw thoughts, feelings, mental images, and perceptions we experience. Consider this medium shot of three characters standing at the train station:

Glinda has worked her way between Fiyero and Elphaba to physically separate the two characters. She had just confided to her friend that she barely knows Fiyero anymore. Since he started “thinking”, he has become “distant” and “moodified”. When Glinda sees Fiyero and Elphaba bonding, she positions herself between them.

Her movement is the plane of expression which conveys her insecurity – the content substance. The audience understands her motivation and what she is trying to achieve.

However, our thoughts are also structured and categorised by systems. The content form helps shape how we interpret the world. In this example, the content substance is influenced by our familiarity with body language and its system of meaning.

Signs acquire their values through their associations and differences to other signs in the system. When Elphaba steps slowly into the Ozdust dancehall, we recognise and appreciate her fear because it is very different to the confidence of Glinda’s graceful movements.

The paradigmatic relationship between “spies” and “scouts” is a really good example of content form. The Wizard of Oz is delighted when Elphaba transforms the monkeys into winged creatures that can fly. He wants to have “spies” who can target his enemies throughout the land. This word horrifies Elphaba, so the Wizard uses the less threatening expression “scouts” instead.

Our understanding of the word “spies” depends on its difference to “scouts”. This is the content form projecting onto our content substance.

Final Thoughts

When we are dancing through life, we take language for granted and simply accept expressions and their definitions. We don’t question why the brick road is yellow.

Sharing his vision of “long and winding paths” across the land of Oz, the Wizard confesses he has “gotten a little stuck trying to figure out what colour the bricks of that road ought to be”. Elphaba flicks the switches, changing the roads from blue to green, yellow, and purple.

Glinda tells her to go back to yellow, claiming, “Yellow just says road to me.”

The media can help develop our understanding of ourselves and the world. However, it also naturalises representations. Roads are yellow. Why would they be anything else?

In media studies, we critically assess expressions to determine their impact, such as how Elphaba is othered in Wicked. Hjelmslev’s model of signs is important because it emphasises the influence of systems on how we present and interpret the world. We can only fully engage with representations if we challenge both the substance and the system.

Hjelmslev wanted a more “scientific treatment” of language to discover the “constancy” of the system. Our focus has been on his sign theory. However, the linguist argued languages “cannot be described as pure sign systems”.

At the most fundamental level, they are “systems of figurae that be used to construct signs”. The function of language is to take marks and physical displays to construct signs.

Bibliography

Hjelmslev, Louis (1961) Prolegomena to a theory of Language. Trans. by Francis J. Whitfield. The University of Wisconsin Press.