GQ Magazine

A study guide for anyone who wants to learn more about the magazine its representations of masculinity, including the cultural and economic context behind the product.

Introduction

GQ claims to be “the flagship of men’s fashion and style” with a “forward-looking, progressive and cutting-edge” approach to making men “look sharper and live smarter”. The lifestyle magazine is an influential mix of award-winning writing and photography aimed at image-conscious young men who are interested in fashion, culture, entertainment, sport, and relationships.

The magazine continues to evolve with an online version at gq.com, a strong social media presence, unique video programming, and tent-pole events, including the iconic British GQ Men of Year Awards which reaches a global audience.

With close analysis of the front cover and a feature from the March 2022 issue, we are going to explore how GQ appeals to the audience and reflects our shifting expectations of masculinity. We will also consider the magazine’s function as a form of advertising and issues regarding media ownership.

Contents

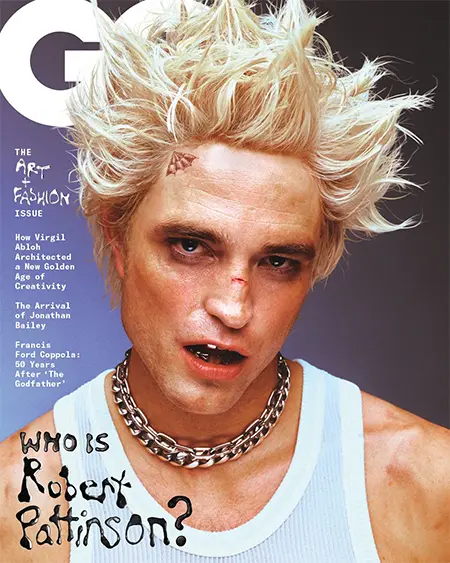

Semiotic Analysis of GQ Magazine

The conventions of magazine covers are immediately apparent on this issue of GQ. First, the dominant signifier is a celebrity who has the star power to attract the interest of the audience intrigued by his glamorous lifestyle. The actor is known for his smouldering good looks, charm, and his high-profile roles in popular films, such as Edward Cullen in the Twilight franchise and the eponymous hero in The Batman.

Pattinson demands our attention with his direct address. Interestingly, the actor subverts his mysterious and intense allure by choosing a more aggressive version of masculinity. A thuggish quality is encoded in his bruised eyes, broken nose, metal-capped teeth, and thick chains around his neck. The carefully spiked hair completes the punk look. That £150 white tank top by Ann Demeulemeester is certainly not glamorous, but the actor remains incredibly charismatic in this photoshoot.

Anchored by the headline “who is Robert Pattinson”, the audience are being positioned to re-evaluate their understanding of the actor. This marketing ploy was particularly important because Pattinson wanted to shake off his boyish persona for his role as the enigmatic Batman. Perhaps the blue gradient background also encodes this sense of transformation.

Notice how the masthead appears behind the actor and the headline is in front of his body. This is another convention of magazine covers. By layering the elements in this way, the designers are trying to imitate a three-dimensional space and ensure the magazine pops out on the shelves.

Commissioned by the publishers in 2000 and developed by Tobias Frere-Jones, the “geometric” design and bold lettering of the title reinforce the brand’s confidence and modern style.

Coverlines reassure the reader the magazine is worth purchasing by highlighting the main features, articles, interviews, and exclusive content. The three coverlines on this issue draw attention an iconic fashion designer, an upcoming English actor, and one of the most famous directors in Hollywood cinema.

It is worth noting the reference to the Jonathan Bailey interview is on the British edition of the magazine – the coverline for the American audience is “The 50 Holy Grails of Modern Menswear”. The publishers simply adapted the content to appeal to the different markets.

Finally, the layout is easy to navigate with a clear hierarchy of information. There is no doubt the designers have communicated the magazine’s brand and content effectively to its target audience.

Genre

In his analysis of popular cinema, Steve Neale defined genre as the “specific variations of the interplay of codes”. This definition also works very well for magazines. For instance, the front covers usually repeat the pattern of presentational devices outlined in the previous section.

Inside, readers will expect the fashion magazine to have content devoted to different types of clothing and accessories. Alongside the interview with Jonathan Bailey, the actor poses in some stylish and expensive outfits. If you wanted to recreate the following look, the Louis Vuitton jacket and trousers cost over £3,000. The Hermès belt was available for £850.

The story is written from the perspective of the interviewer, Douglas Greenwood, who arranged his conversation with the actor in Hyde Park into a coherent narrative. We learn some details about Bailey’s personal life and his acting career – his thoughts on his “avoidant and toxic” protagonist in Bridgerton are useful if you are analysing the representation of masculinity. In terms of genre, this narrative style is typical of longer form magazine interviews. Have a look at our analysis of The Gentlewoman because the Isabella Tree article is another example of this format.

The interplay between the arrangement of text into columns and the high-quality photography is another a key feature of the format.

A Structuralist Approach

Rather than simply being determined by the intentions of individual creators, structuralists argue media messages are part of a larger system of social relationships and cultural values. If we analyse the codes and conventions of magazines, we should be able to develop our understanding of these deeper influences behind the text.

For example, fashion magazines always promote the latest trends in the fashion industry, providing narratives which can influence the clothes we buy in the shops. Jonathan Bailey is wearing his expensive outfits in carefully staged settings, encoding a powerful sense of fantasy and aspiration that will appeal to readers with plenty of money in their designer wallets. However, GQ is dependent on the luxury fashion houses for their support and financial sustainability, so they might prioritise certain designers over others to maintain positive relationships with their advertisers.

You also need to consider how Bailey provides his depth and personality to the designer clothes in exchange for publicity for his own work, especially the second season of Bridgerton. The producers obviously believe readers are more likely to connect with the opinion leader compared to an unknown model because we are already familiar with his rakish identity in the television series. This is another reason why structuralists believe we cannot fully appreciate the meaning of media text until we locate the product in its wider context.

Of course, Bailey’s poses are effortlessly cool which also reinforces the traditional ideal of beauty.

The Constructionist Theory of Representation

Stuart Hall’s work on representation focused on the way meanings are not inherent in language or images, but is constructed through a complex process of selecting, organising, and interpreting information. Emphasising the role of ideology in this process of representation, Hall argued dominant cultural values and beliefs are often naturalised and taken for granted, so we need to resist messages which are hurtful and damaging, especially towards minority and marginalised groups.

Do we just assume Robert Pattinson is a brutish thug because he has a bruised face, spiky hair and wears a heavy chain around his neck? Or that Jonathan Bailey is a suave and sophisticated man ready to make his mark on the world because of his tailored clothes? Perhaps our interpretation of both men depends on our attitudes towards social class.

GQ and Masculinity

In her analysis of feminist discourse, Liesbet van Zoonen (1996) noted masculinity was often defined as individualistic, ruthless, and combative. This gender stereotype was repeated so much in the media it seemed “natural”. However, she also argued gender was a construct and roles will depend on the cultural and historical context.

Perhaps GQ’s focus on male beauty and grooming routines challenges the traditional stereotypes of masculinity. David Gauntlett (2008) certainly believed there was a fluidity of identity when it came to representations of masculinity in the media, including men’s magazines. GQ seems to support his opinion. However, the media theorist also recognised the editors found “excuses to photograph actresses and models in little clothing”, epitomised by Jessica Biel on the cover of the July 2007 issue, and the magazine appealed to “a sense of male specialness with expensive cars, meals, hotels, shoes, grooming products, suits and property”.

If GQ is ideologically dissident in its assumptions about masculinity, it is limited to what the publisher thinks will be accepted by its target audience.

Gender and Performativity

Fashion and beauty were traditionally encoded in the media as feminine, so advertisers had to find ways to make male audiences interested in grooming products. For example, in 1967, the agency behind the Score Hair Cream appealed to the male gaze – buy the product to conquer the glamorous girls. There is a clear binary opposition between the rugged and adventurous man compared to the passive women who hoist him up on the litter.

Judith Butler (1990) described gender as “stylized repetition of acts”. The representation of masculinity and femininity in the Score advertisement is another performance which strengthens the dominant ideology. With its global reach, GQ plays a significant part in this performativity.

Although Edward Pattinson seems unconcerned with his rough appearance on the cover, he is raising questions about common beauty standards and his role as a teenage heartthrob. Jonathan Bailey might be a charming womaniser in Bridgerton, but the actor is content to discuss his homosexuality, saying, “I’d much prefer to hold my boyfriend’s hand in public or be able to put my own face picture on Tinder and not be so concerned about that, than get a part.” The interviewer concludes Bailey is a “sex symbol to many men and women”.

Rather than sparking any gender trouble, the representation of Bailey offers a broader vision of masculinity beyond the old heteronormative values. GQ wants to position itself as part of this evolution of masculinity. You should read Wikipedia’s entry on metrosexuality for more information on the representation of masculinity in GQ magazine and other media texts.

GQ and the Magazine Industry

GQ is published by Condé Nast – a mass media company with a global reach. Founded in 1909, they now own some of “the world’s most iconic brands”, including Glamour, Vanity Fair, The New Yorker, and Vogue. You can read our analysis of Teen Vogue to explore how they target a younger demographic with their digital output.

Condé Nast aims to “entertain, surprise, and empower”. Of course, David Hesmondhalgh (2018) emphasises companies in the cultural industries are driven by profit. Magazines are expensive to produce so mergers are inevitable as the publishers continue to lower their costs and maximise revenue.

In fact, Condé Nast had already been acquired by Advance Publications in 1959 before they took control of GQ in 1979. After a century of investment and acquisitions, Advance’s portfolio also includes shares in Reddit and the media conglomerate Warner Bros. Discovery.

Curran and Seaton (2013) noted this concentration of power in news and information markets has always been a feature of the industry. They are concerned this pattern of ownership enables a few wealthy individuals and families, such as the Newhouse family, to distort the media landscape with their incredible political and economic influence. Another good example of a powerful media family are the Harmsworths who control DMGT and publish The Daily Mail.

However, some critics argue the media moguls do not stifle creativity because they can spread the financial risk and enable producers to develop texts which will satisfy different audiences. This is particularly important with the increasingly intense competition for advertising revenue as more and more consumers get their news and information from online sources.

According to the Audit Bureau of Circulations, the average circulation per issue in the UK was 89,072 in 2021 – down from 110,063 in 2018. Without the efficiencies which come from the larger publishing group, GQ might struggle to reach the shelves in your local retailer.

How Does GQ Make Money?

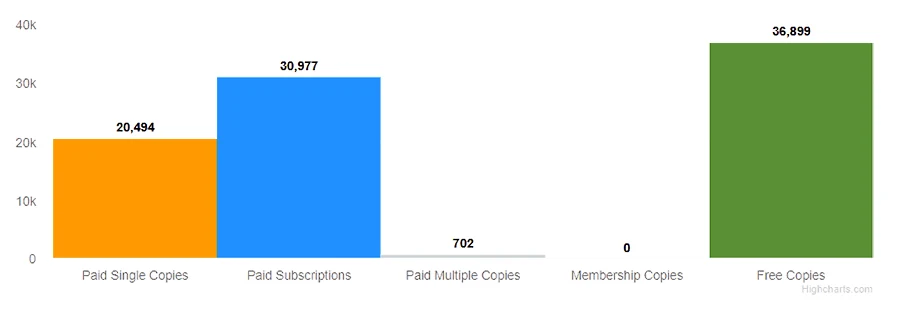

As you can see from the circulation analysis, GQ generates some revenue through single-copy sales and subscriptions. However, the publishers make the magazine available for free because they rely heavily on advertising for revenue, selling space to a wide range of companies eager to target a large and engaged readership.

If you want to raise awareness of your fashion label or grooming brand, an advertisement on the back cover of the magazine costs over £24,000. A double page spread will set you back around £40,000.

GQ’s website also has plenty of room for Google Ads. Scroll down a page about motoring and you will probably see ads for cars loading between the paragraphs and in the sidebar. However, if a company wants to work directly with the magazine, a billboard digital ad costs over £44 CPM (cost per mille). This is the amount the advertising agency pays GQ per one thousand visitors who see the advertisement.

Another important revenue stream is affiliate marketing. The editors select lots of products to review. When you click the retail link and buy something, such as a new pair of shoes or an electric shaver, the magazine will earn a commission.

Finally, GQ also collaborates with retailers and manufacturers to create advertising features which are designed and presented in the magazine’s house style. This advertorial for an anti-ageing product is a good example of this type of partnership. Native articles cost at least £20,000.

Since GQ receives some sort of payment from a brand or retailer for the advertorials, the publisher is required to identify the posts as sponsored. This regulation is overseen by the Advertising Standards Authority who applies its codes across all media to protect consumers from deceptive marketing and help us recognise what is and what isn’t advertising.

Are editorial decisions influenced by the dependence on advertising revenue to offset the costs of producing and distributing the magazine? Is the publisher really acting in the best interests of its audience? Or are the readers actually the product being sold by advertiser-supported media?

GQ’s Target Audience

According to GQ’s media pack, the magazine’s UK audience has a substantial average household income of £138k and, on average, spends £7.7k on fashion and £1.2k on beauty each year. It is no surprise 61% of its readers are classified as ABC1 with junior to higher managerial and professional positions because this demographic tends to have higher disposable incomes.

If you wanted a psychographic label for the target audience, you could describe GQ readers as “activators” from the UK’s Consumer Groups because they have a strong sense of personal identity and are at the forefront of consumer activity. In the cross-cultural consumer categorisation, better known as the 4Cs, the “aspirer” group describes the target audience effectively – materialistic and fashion-conscious with a core need in life for status.

GQ uses the data about its primary audience to demonstrate the magazine is a viable option for advertisers looking to target affluent men interested in travel, technology, grooming, fitness, and fashion.

The Active Audience

Instead of being passive consumers of the media, the Uses and Gratifications Theory proposes audiences are actively engaged in a process of selecting products to satisfy our personal needs and ambitions. According to this model, readers are motivated to purchase GQ magazine to keep up to date about current fashion trends and significant cultural events so they can reinforce their personal identity. The articles might also provide a welcome distraction from their daily lives.

Readers will also interpret the magazine’s content according to their own frameworks of knowledge. Some people will accept the preferred reading and appreciate the “unparalleled coverage of style, culture, and beyond”. Others might take a negotiated position, such as the ignoring the publisher’s liberal stance on many political issues to focus more on the sartorial choices of the politicians. Of course, you might see the £850 price tag for a leather belt and completely reject the magazine’s consumerist message. Stuart Hall called this theoretical decoding position the oppositional reading.

Essay Questions

- To what extent does the representation of gender in magazines embody the dominant values and ideologies in society?

- Explain how the magazine’s emphasis on male beauty and grooming challenges some conventions of traditional stereotypes of masculinity.

- “GQ is a magazine for posh blokes”. Evaluate the usefulness of bell hooks’ concept of intersectionality in understanding the audience’s use of the Close Study Product GQ.

- Albert Bandura suggests audiences develop behaviours and attitudes through modelling by the media. Explore this idea in relation to the Close Study Product GQ.

- Explore how magazines use genre to attract audiences. You should refer to the Close Study Product to support your answer.

- To what extent are editorial decisions influenced by the magazine’s relationship with advertisers?

- How useful are Tzvetan Todorov’s concepts of equilibrium and repair in understanding the narratives in this magazine?

- Explore how GQ continues to engage audiences despite competition from new digital technologies.

Bibliography

Butler, Judith (1990) Gender Trouble.

Curran, J and Seaton, J (2013) Power Without Responsibility.

Gauntlett, David (2008) Media, Gender and Identity.

Hesmondhalgh, David (2018) The Cultural Industries.

Neale, Steve (1980) Genre.

van Zoonen, Liesbet (1996) Feminist Perspectives.

Keep Revising

Get exam-ready with resources and guides designed specifically for the AQA A Level Media Studies specification.