Roland Barthes and Myths

A guide to the signification process and ideological signs.

Introduction

Roland Barthes began writing his “reflections” on “social phenomena” in the mid-1950s. His essays were motivated by “a feeling of impatience” towards the “ideological abuse” of language and representations that reinforced the dominant values of France’s petit-bourgeois elite.

He believed the media and other forms of mass culture were manufacturing versions of reality which the audience were being taught to accept as natural. They were publishing myths – widely held but false beliefs and ideas.

In his first major publication, Mythologies (1957), Barthes delivered his analysis of the hidden assumptions behind a few of France’s most important symbols and attempted to analyse the mechanics of this language.

After a quick look at some of his essays, we are going to focus on his incredibly influential signification process.

Contents

Myths and Mass Culture

Barthes’ description of the many meanings and functions of wine is perhaps the best example of his frustration towards the cultural landscape of the 1950s. If a man did not drink wine, he joked, he would find it very difficult to integrate into French society.

Wine epitomised the brilliant sophistication of the petit-bourgeois culture. Images of wine were being used in the media to signify good health, family and friendship. It often carried connotations of strength, hard work and even purity.

However, by accepting these assumptions, we ignore the many dangers posed by the unhealthy consumption of alcohol. The economics of wine production is also problematic because harvesting the grapes could lead to the awful exploitation of the farm workers who received a pittance for their efforts.

Barthes appreciated the representation of wine is a great marketing strategy but warned his readers the French drinking culture should not be accepted as a natural way of life.

Another essay explored the promotional material for the new Citroën DS depicting the car as a “magical object” that should be worshiped like a goddess. There is no doubt Barthes would be unimpressed by our luxurious car showrooms which really are built like cathedrals preaching a new form of spiritual consumerism and not simply shops peddling a mode of transport.

Barthes also discussed the glamorous appeal of steak and chips. Representations of the dish were constructed to reinforce the myth of France’s superior taste.

Building on the concepts of semiotics devised by Ferdinand de Saussure, Barthes created his own model of signs to help explain the mechanics of language and unmask some of the false and destructive messages we take for granted.

A Working Definition

If you are going to apply the signification process to media texts, you need a secure working definition to support your analysis:

The concept of myth refers to the signs, behaviours and media forms we use to make cultural values and ideologies seem natural rather than socially constructed.

First Order: Form and Concept

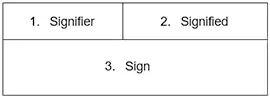

Roland Barthes accepted the argument that signs were bonds between mental concepts and physical forms, but he believed the relationship was one of “equivalence”. That’s why he placed the signified and signifier on the same plane in his diagram.

Anything can be “worked on” to become signs. They could be letters, sounds, pictograms, shapes, colours, photographs, gestures, and clothes. Even flowers can be used to express meanings.

Barthes warned it was wrong to confuse the signifier and sign. He argued the signifier is “empty” because it is just a physical form. The sign is “full” of meaning so it should have its own position in the model.

Barthes merged the term below the signified and signifier because a sign is the “associative total of a concept and an image”. You will also notice he numbered each one to emphasise there are three parts to his system.

Second Order: Myth

A myth is a “brief act of larceny” because it steals the “raw material” of the sign to build its own system. The language-object in first system “becomes a mere signifier in the second” and bonds with a new concept to create a second order sign – the signification.

The full table of this signification process illustrates how the two semiological systems are staggered:

The first order refers to the language we use to communicate our thoughts and feelings. Myths are then “constructed” from this “chain” to give the sign an ideological value.

A few examples will help clarify the signification process.

The Signification of Roses

A rose is a prickly shrub with green leaves and red, fragrant flowers. Some bloom just once in late spring or early summer. Others bloom throughout the summer. They might bear pink, yellow or white flowers, but we are going to stick with an image of the stereotypical red petals.

We can use the physical form of a rose as a signifier and bond it with a mental concept to make a sign. The photograph of a rose might simply denote the shrub and its wonderful flush of flowers in real life, but it could also be used to signify romantic love.

The theme of romance is very pervasive in mass culture, especially in television dramas, rom-coms, song lyrics and popular magazines. It seems every story is a love story. Giving someone a rose feels like a “natural” expression of love and affection, but the gesture is a social convention. It is a myth used to reinforce the dominant ideology of social bonds and family.

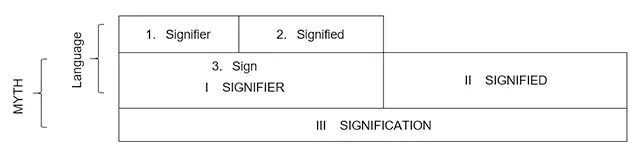

The Signification Cars

Consider the signifier car. The three letters could denote an actual car. Depending on the context, this sign could also signify the concept of mobility and travel. This is the first order in Barthes’ sign-system.

However, the concept of freedom is a dominant ideology in our culture and cars are often encoded with this sense of independence and adventure. In this way, the signification of cars helps naturalise the values we associate with freedom.

The following advertisement demonstrates the link between images of cars and the myth of freedom:

You can clearly see how the producers try to position the audience to connect this car to our desire for individuality and adventure. The rugged mountains and beautiful sky are visually appealing, but they also encode the myth of freedom. This preferred reading is anchored by the words “your epic tale starts today”.

Buy the car and live the dream.

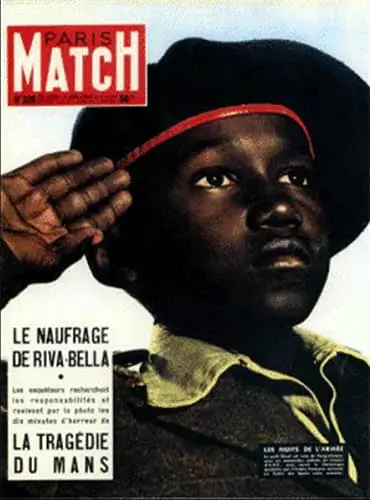

Paris-Match

Roland Barthes picked up a copy of Paris-Match when was waiting in the barbershop to get his haircut. The dominant signifier on the front cover was a young soldier saluting, presumably, the French flag. Barthes felt the image signified “France is a great empire” and “all her sons, without colour discrimination, faithfully serve under her flag”. In other words, the form is the young soldier who conveys the concept of a benevolent French imperialism.

This sign then becomes part of a larger cultural and political narrative which wanted to see France reinforce its military power in Africa and around the world. The purpose for such a positive representation of the boy was to silence the vocal critics of French colonialism.

There were “a thousand images” circulating in mass culture that signified French imperiality at that time. Barthes argued the repetition of the concept in different media forms was an attempt at naturalising the colonial ideology. He was able to “decipher” the myth because it was so prevalent.

Raising the Flag at Ground Zero

The September 11th attacks against the United States of America, and the unthinkable scale of the destruction, shocked the world. Rolling 24-hour news recorded the horrific moments the planes crashed into the Twin Towers in New York and citizen journalists documented the devastation from the streets.

Captured at Ground Zero by Thomas E Franklin, a photographer and journalist, the following image was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in 2002 and was included in Life Magazine’s 100 Photographs that Changed the World.

Denotation

The photograph features a group of firefighters covered in concrete dust. They look exhausted from their tremendous efforts, but they are hoisting the American flag up a pole in the middle of mangled steam beams and rubble from the collapsed buildings.

Connotation

The photograph is a message of defiance and resolve. The American flag becomes the punctum piercing the viewer with a sense of national identity and pride.

Myth

Firefighters risk their lives to safe people in danger. Mass culture often emphasises their heroic qualities to reinforce masculine ideals of strength and self-sacrifice.

The striking red, white and blue of the flag stands out against the grey dust filling the air. It does not seem to be dirtied or ruined by the attack. When Americans wave their stars and stripes (signifier), they are not simply identifying their country (signified), because the flag has become a sign for bravery, independence and self-determination. This level of meaning is another myth, naturalising the ideology that America is the “land of the free and home of the brave”.

FedEx: Neighbours Campaign

FedEx is a logistics company which transports packages across the world with its huge delivery network. Created by DDB Brazil, this Neighbours campaign was designed to communicate its global presence and ability to send goods effortlessly from one continent to another in the same way you can pass a parcel to the people next door.

The story is straightforward: one person is passing a parcel to their neighbour downstairs. However, the map of North and South America painted on the wall reminds the audience that FedEx is a global company that has the capacity to deliver parcels anywhere in the world.

The advertisement reassures the audience that FedEx is reliable and efficient.

Companies like to emphasise the efficiency of their goods and services. Car companies promote fuel efficiency, cleaning products get the job done in a flash, and productivity apps offer speedy multitasking.

Self-checkouts in supermarkets are supposed to be quicker. Fast food is getting faster with click and collect.

Politicians always promise a more efficient health service and rapid response times. Public transportation is praised and criticised for punctuality.

Standardised testing in schools delivers quick and measurable outcomes. Perhaps at the expense of more effective teaching and learning.

This is our contemporary myth of efficiency. A value that has been naturalised around the world. We assume efficiency is inherently good, but it might conflict with other values like understanding, compassion, patience, and creativity.

Myths and Meaning

You will have noticed Barthes identified two orders in the signification process. In the diagram, he labelled the first order language and the wider cultural meaning the myth.

Although myths steal signs to give them ideological values, they “do not hide or flaunt signs”. The function of myth is to “distort” the sign.

Myth does not deny things, on the contrary, its function is to talk about them; simply, it purifies them, it makes them innocent, it gives them a natural and eternal justification, it gives them a clarity which is not that of an explanation but that of a statement of fact.

Roland Barthes (1957)

Myths “naturalise” values, attitudes and patterns of behaviour by making the signs “read as a factual system”. We accept the meanings as self-evidently true even though they are social constructs.

The Transience of Myths

Myths appear and disappear. There is no “fixity”. Mass culture tries to represent myths as natural and eternal to convince the audience to accept the dominant ideology, but they are not fixed or stable.

The colonial powers represented themselves as civilising forces, claiming their values and ideologies were superior to the people they were conquering. The Paris-Match cover suggests subjugated communities welcomed this mission. However, the concept of colonialism is now rejected by the global community.

Times change. So do our values and myths.

Decoding Semiotics

The study of signs helps us understand how meaning is constructed through language. Explore more posts analysing media texts through this critical framework.