The Study of Signs

Our introduction to sign systems will help develop your understanding of how meanings are constructed.

What are Signs?

We use written and spoken language to share our ideas, thoughts and feelings every day. When you ask someone for directions in a busy city or write a fantastic response to a comprehension question in English, you are using words and phrases to communicate with other people. Even the babble from a baby and a teenager’s stroppy grunt can convey important meanings.

However, there are plenty of other ways we can express ourselves, including our body language and movement, choice of music and clothing, images, symbols, colours, and the objects we use to tell stories.

These are all signs.

To analyse a sign properly, you must consider both its physical form and how it might be interpreted. For instance, green is simply a colour, but its definition will depend on the context. If you see green on a set of traffic lights, you know it means go. Green is also associated with youth and vitality. Sometimes, it refers to a lack of experience or to suggest someone is envious. It’s also slang for American dollars.

Contents

This Not A Pipe

Imagine walking into an art gallery and seeing the following painting on the wall. The simple combination of the background colour, the image of the pipe and the caption underneath is very striking. Have good look at the painting and try to decipher the artist’s message.

No matter how long you stare at the painting, you will still see a pipe, yet the artist is declaring “this is not a pipe”. Rene Magritte is forcing the viewer to consider the relationship between the sign and its meaning. In the same way we look at the painting and see “a pipe”, we take the definitions of words for granted.

The physical object is oil on canvas but it makes us think of an actual pipe in real life. As the artist said, “It is just a representation.”

This is not a pipe. It is a sign.

Semiotics

Semiotics, or semiology, is the study of signs we use every day to communicate with other people.

Interestingly, one of the earliest examples recorded of this semiotic process comes from medicine. A doctor needs to identify symptoms before they can diagnose the patient’s illness. Put simply, runny noses and sore throats are signs you are suffering from a cold.

Doctors diagnose illnesses by identifying the symptoms (signifiers) and understanding their meaning (signified)

Four Theorists You Should Know

For your media or communication studies course, you will be expected to explore the physical form of the signs and comment the representation of people and places, so it is important you are familiar with the key terms and concepts of semiotics. The following four theorists were incredibly influential in establishing different models that will help us investigate how meaning is created through the use of signs.

Ferdinand de Saussure

Ferdinand de Saussure was a Swiss linguist who was interested in the fundamental principles of signs that govern language systems.

In Course in General Linguistics (1916), Saussure argued signs had a physical form (signifier) and a concept (signified). By splitting signs into two parts, he demonstrated signs are social constructs and not determined by nature. There is no reason why the word tree should communicate the mental concept of a tree. We have to learn to connect our mental image of a tree to the sequence of letters or sound.

He also argued signs acquired their true values through their syntagmatic and paradigmatic relationships to other signs in the system. For example, we can only appreciate the content of the word tree when it is linked to other words, such as pear tree (syntagm), or when we compare it to bush (paradigm).

Roland Barthes

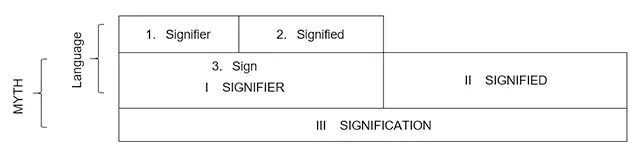

Roland Barthes (1964) accepted the idea that signs consist of a plane of expression (signifier) and a plane of content (signified). The sign is the “relation” between the two planes.

The denotation of a sign is its basic meaning. However, signs can also communicate metaphorical and symbolic meanings that depend on the social and cultural contexts. This is the second level of meaning – the connotation.

In Mythologies (1959), Roland Barthes explored the hidden assumptions behind a few of France’s most important signs, especially those aspects of society and politics which caused him incredible frustration. For example, the signifier of red wine was ideologically important because it signified the importance of family and friendship in French culture.

This signification process consists of two orders:

- language – denotation and connotation

- myth – ideological meanings

When you are analysing a media text, you should critically assess the ideological importance of the signs used to communicate messages and influence the audience’s view of the world.

Charles Peirce

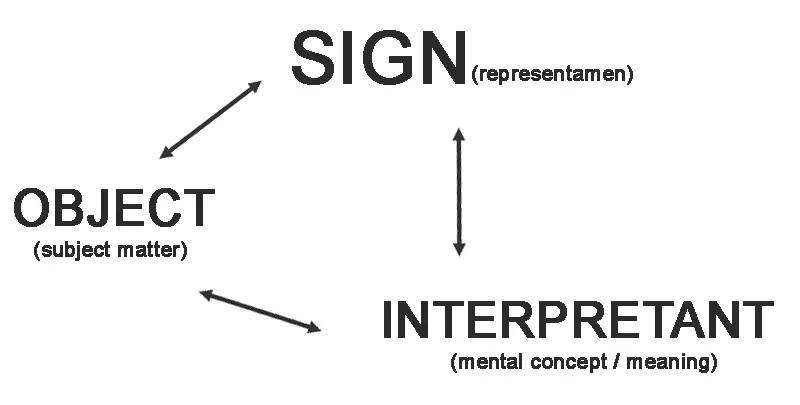

Students often find Charles Peirce’s triadic model of the sign difficult to grasp, but it is a very useful approach to understanding sign processes because it emphasises the importance of context.

The first two parts are similar to the previous models:

- representamen (the physical form of the sign)

- interpretant (the mental concept)

However, each person will have their own interpretation of the sign. This leads to the third part of the model:

- object (the thing in the world the sign refers to)

Meanings are not fixed or stable because everyone will decode the sign according to their own experiences, expectations, and situation.

Peirce divided signs into three categories based on the relationship between the form and the mental concept:

- icon (a physical resemblance between form and meaning)

- symbol (no physical resemblance between form and meaning)

- index (a logical relationship between form and meaning)

His sign categories can help you explore the different meanings encoded in a sign.

Stuart Hall

According to his reception theory, Stuart Hall argued we organise signs into a wider set of values to help us describe and understand the world. Their meanings are not fixed but produced and defined by society.

We all have conceptual maps – the mental representations we carry around in our minds. We translate our mental concepts into signs. However, language relies on convention because there is no natural relationship between signs and their meanings.

If representations are constructs, then we should construct them differently, especially if they are harmful to marginalised groups.

You should also read our guide to his encoding / decoding model of communication.

Signs – A Working Definition

The most concise summary of Saussure’s model of communication comes from Fiske and Hartley (1978) who described signs as a mathematical equation:

signifier + signified = sign.

For the message to be successful, there must be a physical object, such as “sound, printed word or image”, to which a mental concept is added. If either part is missing, then there is no sign and the attempt at communication will be ineffective. This convenient definition of signs should help you engage with the media texts on your course.

Codes

Saussure argued signs secured their definition by being part of a system, or codes. The word “green”, for example, only really makes sense because it belongs to a group of words we use to describe colours. It would be meaningless on its own. Or the colour green on a traffic light is defined by the highway code and its relationship to the other colours.

You can find out more about this concept in our guide to the importance of codes in semiotic theory.

Ideology

The values and ideology of a group of people are often encoded in certain signs that are then repeated in the media. Barthes called this the second order of signification, or myth. Again, our introduction to his signification process offers some insight into this key term, but our guide to ideology and signs will also help clarify the concept.

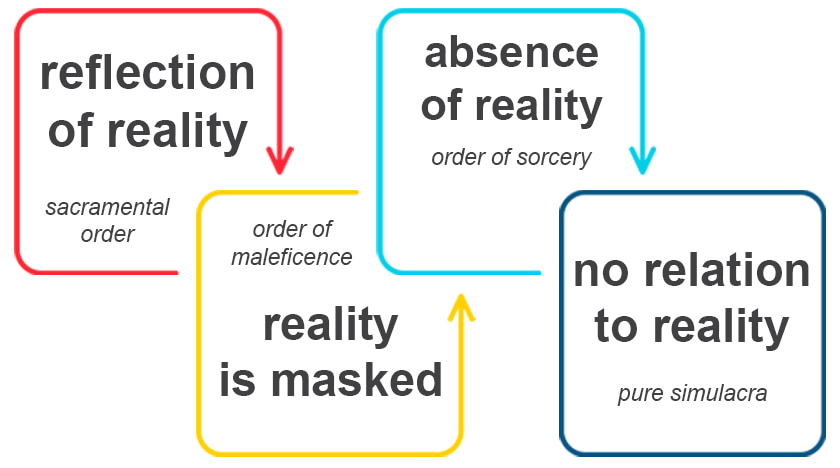

Empty Signs

Jean Baudrillard argued signs were based on the “principle of equivalence”. For instance, the word pipe creates the mental concept of a pipe we might find in the real world. This bond is known in semiotics as the referent. However, the French sociologist drew attention to an implosion of meaning where the relationship between signs and the things they represent has broken down.

This collapse of traditional symbolic systems is clear in the rise of consumer culture and the dominance of media images because signs are now circulated endlessly, losing that connection to reality. Signs no longer have stable meanings. They are increasingly empty. Baudrillard called the final stage of this process the pure simulacra.

Decoding Semiotics

The study of signs helps us understand how meaning is constructed through language. Explore more posts analysing media texts through this critical framework.