Structuralism and the Media

Learn more about the structuralist approach to understanding media texts with our introduction to this important concept.

Definition

If you want to understand culture and how the world works, you should analyse the structures which determine our experiences and behaviour. It is also important to look at the relationships and connections between the different structures to fully appreciate their influence on our lives.

For instance, you can break down Hollywood blockbusters into their codes and conventions to reveal the underlying ideologies which influenced their composition. You might want to see how newspapers can shape public opinion through their technical codes. Or identify the different tactics and appeals advertisers use so you can figure which ones are the most successful.

By analysing the connections between media texts, we can develop general conclusions about the wider cultural context. This approach to studying the world is called structuralism.

Contents

Saussure and Structuralism

Since “we do not communicate through isolated signs”, Ferdinand de Saussure believed signs derived meaning through their “differences” and “groupings”. In our introduction to the linguist’s concepts, we explored the syntagmatic relationship between signs where they can only be understood because “the elements are arranged in sequence on the chain of speaking”. Put simply, words only make true sense in the context of the sentence.

We also considered the paradigmatic relationship where signs are defined by groups. For example, the signifiers “active audience”, “enigma codes”, “broadcast” and “misrepresentation” are all associated with media studies.

We can call Saussure a structural linguist because he argued signs gained their meaning from their relationships to other signs in the language system. The definition of the word “cold” depends on its relationship with the word “hot”. Or your understanding of the word “cottage” is determined by “home” and “barn”. You can then construct very different sentences: “the cottage was cold and dark” compared to “the home was warm and bright”.

Now we know words achieve their real value because they exist within these structures, we can apply the same logic to any other human experience, including the signs used to construct media texts.

Lévi-Strauss and Structuralism

Structuralists try to organise complex ideas into simple and useful data. Although folklore, myths and tribal stories might contain unique characters, settings and action which are important to specific cultures, Claude Lévi-Strauss was convinced the analysis of their narratives might reveal some insight into the universal human condition.

In his attempt to understand why there was an “astounding similarity between myths collected in widely different regions”, Lévi-Strauss took the structuralist approach and divided the stories into fundamental units he called the mytheme. For instance, he noted the trickster archetype was often represented as a raven or coyote in Native American myths. This links the role of characters in the stories to animals who like to scavenge for food. You can draw your own conclusions about the use of this motif in the myths.

After collecting and analysing the data, Lévi-Strauss concluded all cultural practices had deep, underlying structures which often manifested themselves as binary opposites.

Binary pairs, particularly binary opposites, form the basic structure of all human cultures, all human ways of thought, and all human signifying systems…

Claude Lévi-Strauss

Vladimir Propp

Another example of structuralist approach to understanding stories comes from Vladimir Propp who designed a way to analyse the fundamental properties of Russian folktales. After searching 100 stories for underlying patterns, Propp noticed the narratives did contain “constant elements” which could be expressed in terms of the characters’ functions.

Propp identified seven character types and thirty-one distinct functions. His narrative theory remains incredibly popular and features on lots of media studies courses.

Putting the Theory into Practice

Consider how the following film poster combines culturally important signs to construct a message which the audience will easily decode:

In order to make sense of the artwork, you have to think about the dominant signifiers and how they are being arranged in the composition. You should already know enough about media language to guess this poster is focusing on a battle between good and evil because it follows some straightforward rules and principles.

In terms of dress and colour codes, there are two characters dressed in white, suggesting they are the heroes. The black clothes encode Darth Vader as the villain. Hans Solo, who has a black waistcoat over a white shirt, is the morally ambiguous trickster in the story.

The colours of their weapons are also different – a lurid orange versus the glowing pink. Notice how the villain is in a menacing position behind and above the heroes. His large presence helps establish the threatening tone.

Finally, there are plenty of signs which indicate the film is set in space – spaceships, lasers, robots, an alien, and the fact the title is “Star Wars”. This will be a battle of galactic significance.

By analysing the signs, we can make some assumptions about the narrative. From a structuralist perspective, does the poster suggest we worry about the forces of good an evil in our own society?

Another Worked Example

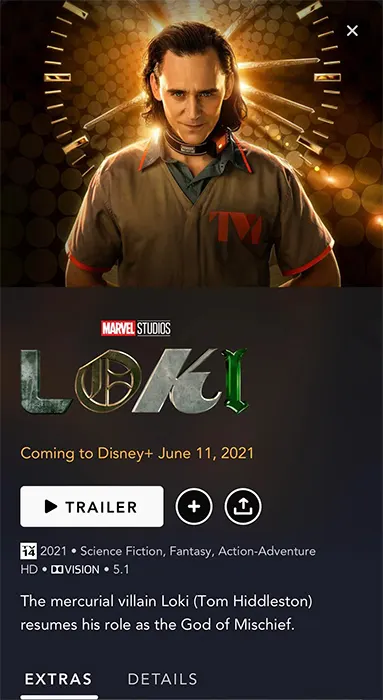

Since we have already referred to tricksters, it is worth considering one of the most popular mischief-makers in contemporary storytelling – the Norse god, Loki. The following thumbnail and content detail comes from the Disney+ interface.

How does this text point to the wider human condition? Again, let’s take a semiotic approach. The use of the gold colour code points towards the character’s divinity and power. This is reinforced by the halo effect.

However, that is an electronic tag around his neck signifying his villainy. His direct address is an aggressive challenge to the audience.

There is a moral ambiguity to the character which is typical of the “mercurial” trickster archetype. Does this representation suggest a wider internal conflict we have all experienced? A tension between the desire to do good or act in our own self-interest?

Decoding Semiotics

The study of signs helps us understand how meaning is constructed through language. Explore more posts analysing media texts through this critical framework.