Studium and Punctum

Develop your understanding of Roland Barthes’ two fundamental themes of photography with these definitions and examples.

Introduction

Roland Barthes was keen to “formulate the fundamental feature” which gave photography its “essence”. Investigating the impact of photography on the observer, he distinguished two themes: the studium and the punctum. The studium is the social and cultural interpretation of the photograph and the punctum is a specific detail which provokes a deep and personal reaction to the image.

Published two months before his death in 1980, “Camera Lucida” remains a fascinating discussion of the nature of photography. This guide focuses on some of his key thoughts.

Contents

The Studium

Photojournalists report stories, portrait photographers capture the personalities of their subjects, and we all point the lenses on our phones to document our own stories. We can learn about the world from the “figures, the faces, the gestures, the settings, the actions” we observed in those images. For instance, Barthes believed photographs were a “kind of education” because they helped us visualise “good historical scenes”.

He called this level of engagement with photographs the studium.

Barthes felt the Latin word studium was an appropriate label because it denoted an eagerness and enthusiasm towards studying, recognising both the intentions of the photographer and our desire to become more informed about the subject.

The Punctum

Barthes said he would “occasionally” be attracted to a specific “detail” in a photograph and its presence would have a tremendous impact on his reaction to the image. He wanted a different term for “this wound, this prick, this mark made by a pointed instrument”. He called this “detail” is the punctum.

Everyone will have their own interpretation of a photograph. Some might be indifferent to the subject. Others might be marked by an “unexpected flash”. Therefore, the punctum is a “higher value” added to the photograph by the observer. It is the direct and powerful relationship between the observer and a particular signifier in the image.

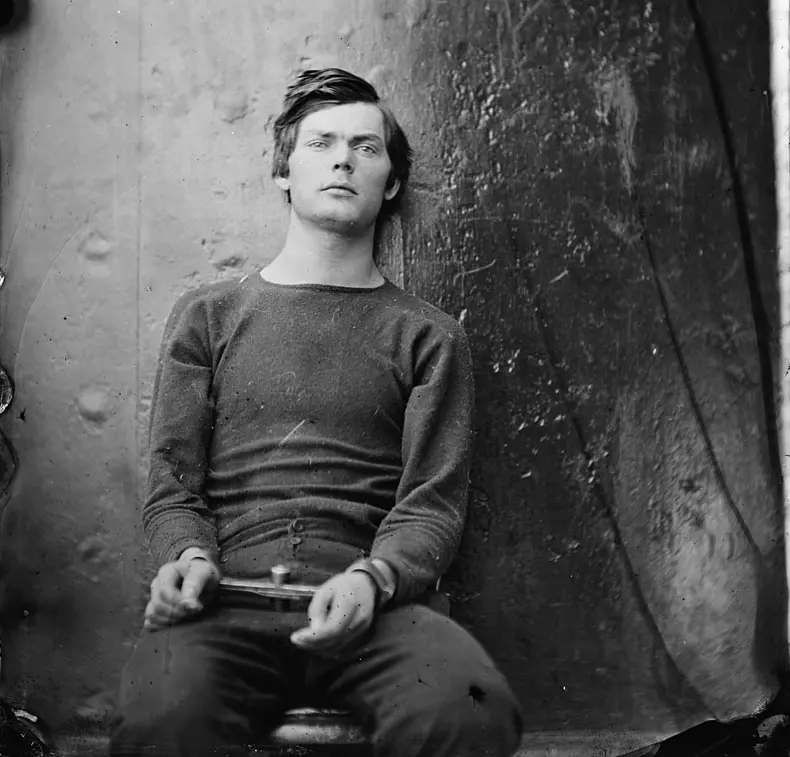

The Portrait of Lewis Payne

Barthes offered a number of examples to explain the difference between the studium and the punctum. We are going to consider the portrait of Lewis Payne.

Lewis Payne was a Confederate soldier and one of the conspirators who planned the assassination of the American president, Abraham Lincoln. This photograph was taken in his cell where he was waiting to be hanged for his brutal attack on the Secretary of State, W.H. Seward.

Barthes described the photograph and the young man as “handsome”. There is something heroic in his defiant gaze into the distance and the way he leans back against the canvas. The handcuffs are a reminder of his terrible crime.

The photographer, Alex Gardner, knew he was documenting this important moment in American history. Transporting the observer back to 1865, the photograph still draws attention to the young man’s role in the complex conspiracy to murder the president. This “historical interest” is the studium.

The punctum is usually a specific signifier in the photograph whose impact might be “revealed only after the fact” when you think back to the image. However, in this example, Barthes felt pierced by the fact Payne was executed just over two months after this photograph was taken. The horror of knowing “he is going to die” is the punctum.

The Detail

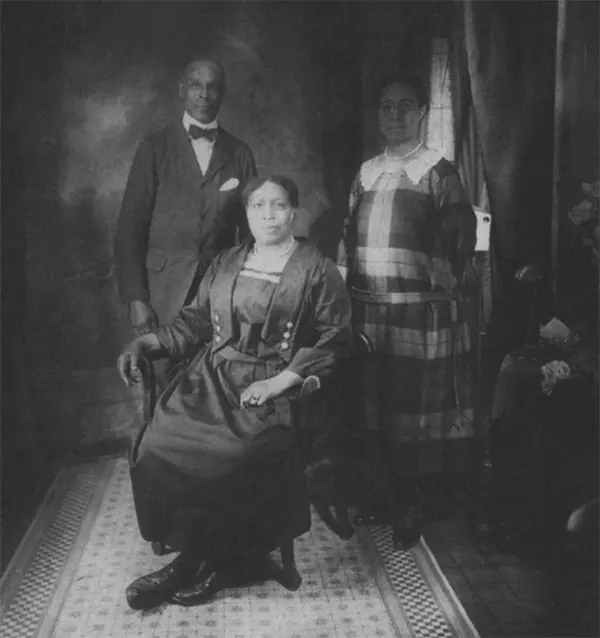

In most other examples, Barthes focused on signs which were piercing, such as the “tenderness” of the “strapped pumps” and the “belt worn low” by the woman with the crossed arms in the following photograph. He felt these details connoted “respectability, family life, conformism, Sunday best” and “an effort of social advancement”.

The punctum is “quite often” a “partial object” but it is powerful enough to provoke a “higher value” response from the observer. Remember, everyone will have their own reaction to a photograph, so you might be pierced by other signifiers in the image. Look at the way the rug runs parallel to the tiles. That precision is also very striking and conveys the incredible pride the family take in the presentation of their home.

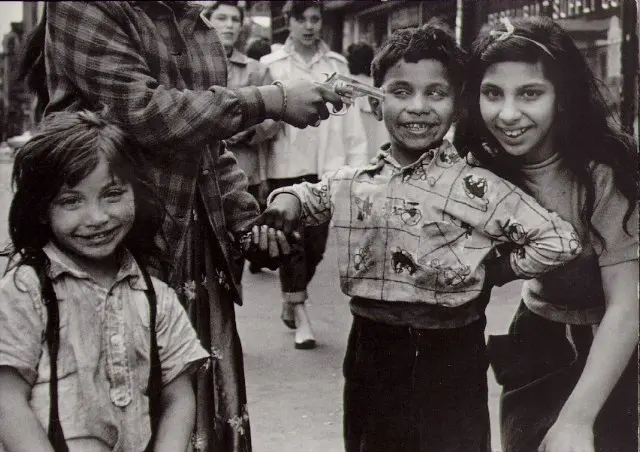

Barthes also admitted the punctum might be “ill-bred”. For instance, he knew it was inappropriate to “stubbornly” focus on the boy’s “bad teeth” in this particular photograph:

Photography and Semiotics

Barthes stressed how “every photograph is somehow co-natural with its referent” and that “the photograph is literally an emanation of the referent”. He argued painters can “feign reality” but “something had to be placed before the lens” for the photographer to take its picture.

Since photographs are never distinguished from what they represent, Barthes wondered if the images were simply accidents and could not signify anything “except by assuming a mask”. He even suggested it was safer to accept photographs carried no meanings at all. This is certainly an interesting perspective if you are studying the media because we often argue producers carefully construct meanings.

However, he also noted the photographer points their camera and “limits, frames, and perspectivizes” the world. Therefore, the studium is always coded. By contrast, the punctum is an accident beyond the control of the photographer and cannot be coded.

Barthes’ signification process is still a useful framework to analyse a photograph, especially when you are exploring the physical form of the punctum.

The Abundance of Images

If the studium is “the order of liking”, the punctum is “the order of loving”.

When you are scrolling through photographs on your device, what makes you stop flicking and study a picture in more detail? Perhaps it is the visual style or the vibrant use of colour. Your attention might be grabbed by a familiar face or an interesting caption, so you look closer and read the image. This is the studium.

Long before social media platforms began to dominate our lives, Roland Barthes commented “everything” was being “transformed into images” and that the punctum was “more or less blurred beneath the abundance of contemporary photographs”.

The next time you are deeply affected by a photograph, think about the specific detail which has provoked this profound reaction because that is the punctum.

Bibliography

Barthes, Roland (1981) Camera Lucida: Reflections of Photography. Translated by Richard Howard.

Decoding Semiotics

The study of signs helps us understand how meaning is constructed through language. Explore more posts analysing media texts through this critical framework.